Well, 2019 was a bit bumpy, wasn’t it? As always, I took refuge from the vicissitudes of the UK’s fortunes with a lot of good books. Looking over my list this year, it’s quite heavy on dystopia, with some unflinching real life reportage and a top-note of hope.

Well, 2019 was a bit bumpy, wasn’t it? As always, I took refuge from the vicissitudes of the UK’s fortunes with a lot of good books. Looking over my list this year, it’s quite heavy on dystopia, with some unflinching real life reportage and a top-note of hope.

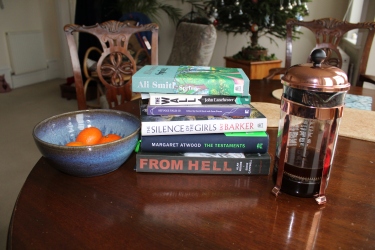

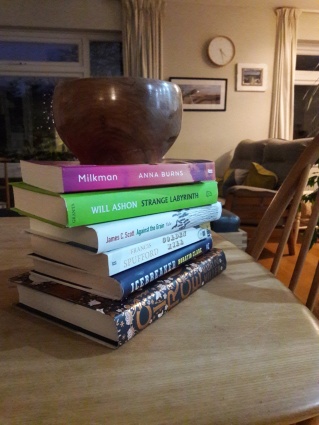

In no particular order, I enjoyed:

1. John Lanchester, The Wall. An all-too-believable future Britain, grimly keeping out the Others. Beautifully written, with the best exploration of cold and boredom I have ever read. Sure, it was bleak, but the humour and humanity kept me gripped to the bitter end.

2. Margaret Attwood, The Testaments (and The Handmaid’s Tale). I began by re-reading The Handmaid’s Tale, which I first read more than 25 years ago, before diving into The Testaments. In both books I was most interested in the way Attwood showed how oppressive regimes maintain their position by exploiting our fear and self-interest. Everyone thinks they would resist – but would we really?

3. Various authors, Refugee Tales III. The latest edition of stories from around the world, washing up on our shores. You can’t think of someone as other when you’ve listened – really listened – to their story.

4. Alan Moore, From Hell. Graphic novels are well outside my usual comfort zone. I read this for research for my next novel, and found it unsettling, gripping and immersive. From Hell was a tough one, with far more horror (graphically depicted) than I usually read. But a forcible introduction to the genre.

5. Anna Burns, Milkman. God, I loved this book. The unmistakeable voice of the narrator, the absurdity of the humour, the all-enveloping claustrophobia within which horrors that would be tolerated nowhere else seem normal.

6. Toni Morrison, Jazz. I’d not read this novel until Morrison’s death was announced this year. The obituaries sent me back to her output, and I had my eyes opened to the formal inventiveness of her work, especially in this spiky, riffing, cut-up novel of life on the edges of New York’s Harlem.

7. Ali Smith, Spring. Third in the quartet of seasonal novels from Smith, and the one that takes her closest to the Refugee Tales project, of which she is patron. Her experience of visiting the detention centre at Gatwick comes through clearly in this novel of hope, redemption and the power of stories.

8. Kerry Hudson, Lowborn. I was lucky enough to catch Kerry Hudson talking about her visceral memoir at the Bookseller Crow independent bookshop in Crystal Palace this year. It will break your heart and re-make it, with a bit more space inside.

9. Diana Evans, Ordinary People. More Crystal Palace memories, just as I leave the place where I’ve lived for the past 17 years. An ordinary love story set among ordinary people in an ordinary London suburb. In extraordinarily clear prose, it explains why love is not always enough.

10. Pat Barker, The Silence of the Girls. This was the book that started my year – an astonishing conjuring-up of the stink and guts of war, and the misery that it inflicts on the non-combatants – the women, the children, the girls.

This midwinter, I’m reading Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising, along with the peerless landscape author Robert Macfarlane and thousands of others on Twitter (#TheDarkIsReading if you want to join in).

This midwinter, I’m reading Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising, along with the peerless landscape author Robert Macfarlane and thousands of others on Twitter (#TheDarkIsReading if you want to join in). Sydenham Hill woods was once part of the Great North Wood that covered this part of south London. It’s a domesticated suburban woodland now, but the backbone of the forest is still there; the soaring trunks of oak and hornbeam, straight and dark in the damp air, raising their bare canopies to the skies. Sombre holly hunches beneath (few scarlet berries this year), intertwined with glossy ivy.

Sydenham Hill woods was once part of the Great North Wood that covered this part of south London. It’s a domesticated suburban woodland now, but the backbone of the forest is still there; the soaring trunks of oak and hornbeam, straight and dark in the damp air, raising their bare canopies to the skies. Sombre holly hunches beneath (few scarlet berries this year), intertwined with glossy ivy.